Smart Key: Elasticity: What’s the environmental impact of the elastane in our clothing? The - Yarns and fibers

Elastane represents just 1% of the world’s fiber production. Given such a low production volume, it’s easy to underestimate its impact. Yet the reality is that this extraordinarily stretchy fiber is found in the vast majority of products. At 60 years old, elastane is now ubiquitous. Just what distinguishes this queen of comfort fibers, and what are its environmental impacts?

Liberating the body with elastane

During the scandals and revolutions of the early 1900s, visionary couturiers Madeleine Vionnet and Paul Poiret set themselves off by creating fluid silhouettes through bias cuts and high waistlines, thus liberating bodies previously constrained by corsets.

This fluidity resurged again in the late 1960s. The 1970s marked the liberation of women, highlighting bodies freed from all constraints, including restrictive apparel. Developed in the 1960s by Dupont de Nemours, elastane was a substitute for natural rubber but with superior physical properties, and was quickly poised to usher in the next wave of transformations. Also known in the U.S. as spandex – a catchy anagram of ‘expands’ – this petrochemical fiber, a derivative of polyurethane, became synonymous with elasticity.

Its initial uses in the 1970s were in sportswear, enhancing freedom of movement with products designed to mold to the bodies of cyclists, gymnasts and dancers.

By 1978, improved qualities were rolled now boasting increased resistance to chlorine and bleaching. The following decade saw its expansion beyond sports gear. In the 1980s, elastane became the emblem of the era’s fitness craze, shaping the iconic looks of a decade where bodies were toned and supple. Elastane dominated everyday wear, slipping into the construction of jeans, skirts, tops and lingerie to enhance ease of movement.

Prisoners of comfort?

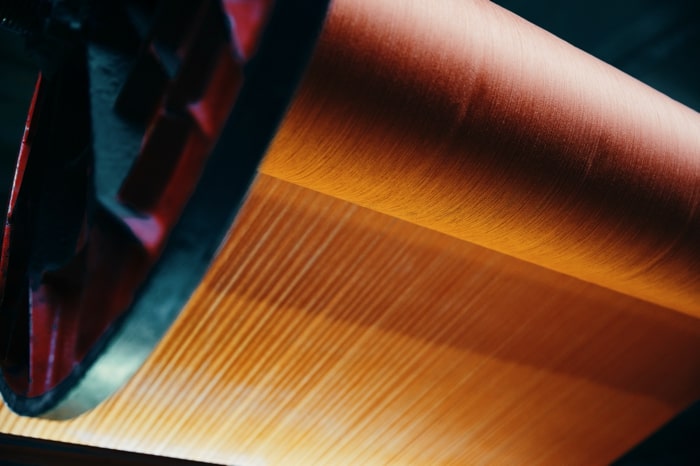

This synthetic elastomer is obtained by dissolving polyurethane in a solvent, then treating it with silicone-based oils to reduce the fiber’s adhesive properties. Elastane can stretch 400 – 700% and still revert to its original size. This advantage, coupled with the ability to produce very fine yarns, enables the development of high-performance technical products including featherweight second-skin lingerie.

However, this fiber also ticks several problematic boxes associated with the development of synthetic materials: petroleum use and high energy consumption. In addition, the heavy chemical treatments involved in its transformation include the use of solvents such as Dimethylformamide (DMF), which can cause liver damage and present a reproductive risk, and the diffusion of toluenes into the air, which, in the case of chronic exposure, can lead to impaired lung function. Conventional elastane is also non-biodegradable and persists for hundreds of years in the environment. It also hampers recycling by disrupting the fraying process during mechanical recycling.

If conventional elastane poses a hurdle to the development of low-impact products, what alternatives should we consider?

Smart Key #1 : Opting for naturally stretchy properties

It’s not about giving up on the comfort we’ve enjoyed in recent decades, but rather rethinking how we use materials. The mechanical performance of certain yarns, weaves and fibers can provide comfort without the need for elastane.

Crepe yarns, with their very high twist, allow us to play with their “springy yarn” qualities. Crêpe weaves are also worth exploring, as their specific construction creates an irregular effect and offers significant elasticity. Among natural fibers, wool stands out due to its inherent curliness, offering natural elasticity.

Smart Key #2 : Banking on next-generation elasticity

Since its invention, elastane has undergone a number of innovations to offer new, lower-impact features, while retaining its significant stretch capacities.

To reduce dependence on fossil resources, some elastanes are currently formulated with a proportion of bio-sourced content, notably corn dextrose and castor oil.

Another possibility is recycled elastane, developed with up to 60% recycled content from production waste.

With a focus on the overall product life cycle, biodegradable elastane such as Roica™ V550 are innovatively designed to break down faster than their conventional counterparts, without leaving harmful substances in the environment.

Smart Key #3 : Optimizing blends to promote recyclability

The first criterion to bear in mind in terms of blended compositions is using a low percentage of elastane, i.e. 1- 2%. Over 5%, elastane becomes a major obstacle to mechanical recycling, as the fabric becomes “elastic” and resists the rollers used to fray it.

In terms of recycling synthetic textiles – though this is relatively undeveloped at present – certain materials are more suitable for recycling.

Polyester and polyester-type polymers, such as Sorona® PTT and Lycra T400® elastomultiester, are also elastofibers. By using them in conjunction with polyester as the main fiber, recycling capability is improved thanks to their similar natures, enabling the obtention of homogeneous material deposits.

So, do we stretch the planet’s limits or maximize our comfort? As is often the case, the answer isn’t a drastic choice between one or the other. Instead, it involves finding the flexibility to assess the situation, reserving petrochemical-derived materials for technical uses, and avoiding resorting to them without careful consideration, given that other alternatives are available to us.

Sources

• N, N-Dimethylformamide, Toluene toxicological data sheet database – INRS, Institut National de Recherche et de Sécurité.

• Substance Infocard N,N-Dimethylformamide; Toluene – ECHA, European Chemical Agency

• Study on the factors disrupting and facilitating textile and household linen recycling – École Nationale Supérieure des Arts et Industries Textiles for EcoTLC – July 2014